You Can Go Home” Officers Told German Female POWs — But They Begged To Stay in the U.S.

May 8, 1945, marked the end of the war in Europe—a day of jubilation that reverberated across the world. In London, Paris, New York, and beyond, Victory in Europe (VE) Day was celebrated with fireworks, parades, and tears of relief. But for thousands of German female prisoners of war (POWs) held in American camps, the news was not greeted with the kind of euphoria one might expect after years of brutal conflict. For them, the announcement that the war had ended came quietly—amid the clang of barbed wire and the somber rhythm of daily life within the internment camps scattered across the Midwest.

The American officers stood before the assembled prisoners, men and women alike, and simply said, “You can go home.” The words should have been a liberating call to action, a long-awaited promise of freedom. Yet, as the officers spoke, a strange silence fell over the camp. The German women, many young and some older, exchanged glances, their faces betraying not the joy of liberation, but the confusion and fear of the unknown.

Some shook their heads in quiet disbelief, others murmured softly in German, “Nein.” For them, freedom had become a distant concept—a shadow of the harsh, uncertain realities they had lived with for so long. The idea of returning home, to a country shattered by war, was a notion that felt perilous rather than comforting.

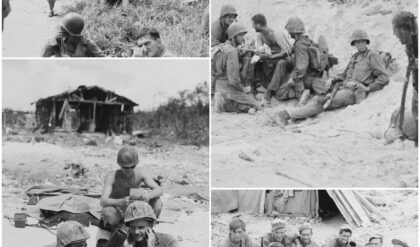

The women had been brought to America under suspicion and fear, and their experience had been shaped by a mixture of propaganda and the horror of wartime atrocities. Yet, during their months in the American Midwest, their expectations had been completely upended. The German POWs had assumed the worst: that they would be treated harshly, perhaps with the same kind of brutality they had been led to expect of the American forces. But what they encountered in these camps was nothing like they had imagined. Instead of the harsh conditions they expected, they found a level of order, cleanliness, and, most surprisingly, generosity. The American soldiers, many of whom had experienced their own traumas during the war, now found themselves responsible for the care and welfare of their former enemies.

The experiences of these women in the POW camps reveal much about the complexities of war, human dignity, and the surprising nuances of post-war rehabilitation. It is a story not just of prisoners and captors, but of women navigating the emotional and psychological aftermath of war, facing the uncertainty of a world where everything they knew had been upended.

The Women Behind the Barbed Wire: Who Were These POWs?

The German female POWs were not one homogeneous group; their backgrounds varied as widely as their reasons for being imprisoned in the first place. Some were young women conscripted into the war effort, working as communications auxiliaries for the Luftwaffe (the German Air Force), performing clerical duties that kept the military’s communication lines open. Others had served as nurses, caring for the soldiers on the front lines. Some, however, had no direct ties to the military but were swept up simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. They had been arrested for minor infractions or for working too close to certain units, often based on little more than suspicion.

Nazi propaganda had portrayed the Allies, particularly the Americans, as merciless and brutal—the very antithesis of the civilized, cultured German ideal. The women who found themselves in American custody had been conditioned to believe that their captors would treat them with cruelty. This belief was further reinforced by the journey across the Atlantic. Many had endured difficult, uncomfortable conditions aboard gray-painted troop ships, shrouded in dread and uncertainty about their fate.

Yet, when they arrived in the American POW camps, their preconceived notions of brutality were shattered. What they found, to their astonishment, were clean barracks, orderly routines, and a surprising abundance of food—an overwhelming departure from the starvation and deprivation they had been accustomed to back home. The sight of fresh, wholesome food like peanut butter—a strange, sticky substance they had never encountered before—was a revelation to many of the women. One young prisoner, only twenty-two years old, wrote in her tattered notebook, “They feed us peanut butter—sticky, strange, but rich. I cannot stop eating it.” For her, the small act of nourishment felt almost like a betrayal—a stark contrast to the harsh realities of war and scarcity she had known before.

Some women, who had been forced to wear worn-out shoes for years, received new footwear upon their arrival in the camps—another unexpected kindness. These seemingly small comforts highlighted the vast difference between the life they had left behind in Europe and the life they were now experiencing in America. It was a jarring juxtaposition—one that made their return home feel even more uncertain.

The Dilemma of Going Home: The Psychological Burden

For many of these women, the announcement that they could go home was not a moment of joy but one of fear and uncertainty. The idea of returning to Germany was fraught with emotional complexity. Germany had been decimated by years of war; its cities lay in ruins, its people were suffering from hunger and devastation, and many of these women had lost family members or had been separated from their loved ones. Some women had even seen their families die or disappear in the wake of the conflict, leaving them with no real sense of belonging or direction.

The women were caught between two conflicting realities: the desire to return to their homes and the fear that doing so would plunge them back into a world that was irreparably shattered. Some of them had been captured in the final stages of the war, and their experiences of captivity in America were far from what they had expected. They had been fed, treated with basic dignity, and even given a sense of safety—things they had never imagined possible when they first set out for the front lines in Germany. The thought of returning to a world of bombed-out buildings, cold winters, and a country in turmoil was more than they could bear.

For these women, freedom didn’t feel like salvation—it felt like another daunting chapter to face. They had been prisoners of war, but in many ways, they felt just as trapped by the uncertainty of their future as they had been under the control of the German military. Their lives were forever changed by the war, and returning to a broken homeland was not the reunion they had imagined in their dreams.

The Role of American Officers: Compassion Amidst Conflict

The actions of the American officers who managed the POW camps in the Midwest during the post-war period are a poignant reminder of the humanity that can exist even in the most harrowing circumstances. For the American soldiers, these camps were not just places of containment—they were also places of rehabilitation and recovery. These soldiers were tasked not only with maintaining order but with ensuring that the women were treated with dignity, even as former enemies.

The officers’ approach to their captives was surprisingly compassionate. They recognized that, though these women were technically “enemies,” they were also human beings who had suffered as much as anyone else in the war. The fact that the American forces extended their kindness and compassion to these women—feeding them well, providing basic comforts, and allowing them to recover physically and emotionally—speaks volumes about the kind of people who served in the U.S. military during this time. The treatment of POWs was often a reflection of the values that the Allies had fought to defend, and the women who found themselves in these camps were given a glimpse of the kind of world they had been fighting against.

While some of these women may have been reluctant to return to Germany, the kindness of the American forces helped to ease their transition. The officers didn’t just offer food and shelter—they offered something even more powerful: a sense of humanity.

A Complex Ending: The Paradox of Freedom

When the announcement came that the war was over and the women could go home, it was supposed to mark the end of a long and painful chapter in their lives. But instead, it marked the beginning of a new, complicated struggle—one where freedom was not easily accepted, and where the psychological wounds of the war would take much longer to heal.

For the women who had been imprisoned by the Nazis and then held as POWs by the Americans, the idea of going home was no longer straightforward. It wasn’t just about returning to a country—it was about reconciling the emotional scars of war, the loss of family, and the uncertainty of what lay ahead. Their journey back to Germany was not just a physical one; it was a journey of emotional and psychological recovery, and in many ways, it was a journey that would last a lifetime.

The Power of Compassion and the Weight of War

The story of the German female POWs in the American Midwest is one that reveals the complexities of war, survival, and human compassion. While the women’s experiences as captives were born from the destruction of conflict, their treatment by the American forces reflects the humanity that transcends the boundaries of battle. Despite the horrors they had faced, the kindness extended to them during their time in captivity became a profound reminder that even in the most difficult of circumstances, there is always room for compassion.

As these women returned to their shattered homeland, they carried with them not just the physical scars of war, but the emotional weight of the choices they had been forced to make. And while freedom may have seemed like the ultimate prize, it was the compassion and humanity they experienced in the American POW camps that left a lasting impression—a reminder that, even amidst war, kindness has the power to heal and transform.