The Day Eisenhower Stopped Tolerating Montgomery: A Showdown That Changed the Course of WWII

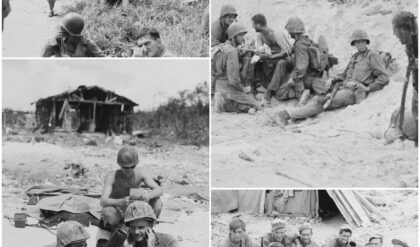

The morning was still dark when Dwight D. Eisenhower first laid his eyes on the telegram. As the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force during World War II, Eisenhower had grown accustomed to the weight of responsibility and the delicate art of navigating the complex dynamics of the war effort. But when the message arrived from General Bernard Montgomery, it was different. At first, Eisenhower thought he must have misunderstood the contents—surely, this could not be a real demand.

The telegram from Montgomery, one of the most famous and sometimes controversial generals of the war, was a direct and unapologetic request for more resources—more men, more equipment, and more authority. The kind of request Eisenhower had grown increasingly unwilling to entertain. Montgomery’s demands, which he had made before, had always been pushed through diplomatic channels. But this time, the tone of the telegram seemed to cross a line. It wasn’t just a request; it felt like an ultimatum.

Eisenhower, who had spent much of the war balancing the egos of his fellow generals, coordinating a multinational effort, and keeping the Allied forces united, could sense that something was shifting in his relationship with Montgomery. And this telegram, this final demand, was the moment that would mark the beginning of the end of their collaboration.

The fallout from this exchange would resonate throughout the military leadership of the Allies, with Eisenhower’s decision to stop tolerating Montgomery’s behavior marking a pivotal moment in their relationship and, ultimately, in the execution of the war effort. But this wasn’t just a conflict between two men—it was about leadership, power, and the evolving strategy that would determine the course of World War II.

The Background: Eisenhower and Montgomery’s Complex Relationship

Eisenhower and Montgomery had always shared a complex relationship. On the surface, they both shared the same goal—defeating the Axis powers—but their approaches to achieving that goal were starkly different. Eisenhower was known for his ability to unite a coalition of nations, balancing the needs and expectations of British, American, and other Allied forces. His diplomatic skills were unparalleled, and he had a reputation for being a calm, steadying presence in the face of intense pressure.

Montgomery, on the other hand, was a general who believed in decisive action. He was fiercely confident in his abilities, often to the point of arrogance. His tactics were meticulous, and he often demanded total control of his forces, sometimes to the detriment of the broader Allied strategy. While Montgomery’s successes, particularly in North Africa, had earned him respect, his personality and leadership style frequently put him at odds with his peers, especially Eisenhower.

The tension between the two men was often palpable, with Eisenhower having to walk a fine line in managing Montgomery’s ego while also ensuring that the overall war effort remained cohesive. Montgomery’s stubbornness and desire for recognition often clashed with Eisenhower’s more diplomatic approach to leadership, and it was this growing friction that would eventually lead to the moment when Eisenhower decided he could no longer tolerate Montgomery’s demands.

The Telegram: Montgomery’s Demand for More

In the weeks leading up to the invasion of Normandy and the subsequent push through France, tensions between Montgomery and Eisenhower had been building. Montgomery had always been vocal about his desire for more resources, more control, and more recognition for his role in the campaign. But when the telegram arrived in Eisenhower’s office, it wasn’t just a polite request—it was a demand. Montgomery asked for a substantial increase in resources, including additional troops, tanks, and artillery, as well as the power to make decisions without consulting Eisenhower.

Montgomery had, in effect, asked for more autonomy, more power, and more support, but the timing of the request was significant. The Allied forces were already stretched thin, and Eisenhower, as the supreme commander, had to maintain a delicate balance in coordinating the contributions of the British, Americans, and other Allies. The sheer audacity of Montgomery’s demand, especially after the successes of D-Day and the ongoing push through France, struck Eisenhower as an overstep. It wasn’t just a military request—it was a personal affront, questioning Eisenhower’s authority and judgment at a crucial juncture in the war.

Eisenhower’s initial reaction to the telegram was disbelief. He had always been a patient leader, known for his ability to work with difficult personalities, but this request felt like the tipping point. The communication was blunt, and Montgomery’s usual bravado was on full display. He seemed to be suggesting that the success of the campaign could hinge on his ability to operate with more autonomy—an implication that Eisenhower, who had worked tirelessly to maintain unity within the Allied command, found intolerable.

The Breaking Point: Eisenhower’s Decision

As Eisenhower sat with the telegram in his hands, the weight of his decision began to settle over him. He had always respected Montgomery’s abilities as a general, but this was different. It wasn’t just about military tactics—it was about leadership. Montgomery’s refusal to work within the established chain of command, his insistence on more power, and his willingness to bypass Eisenhower’s authority struck at the heart of what Eisenhower had worked so hard to maintain—unity among the Allies.

Eisenhower knew that he had to make a decision, and it wasn’t going to be easy. Montgomery was a popular and highly respected general, particularly among the British forces. To remove him or to limit his role would be a political and diplomatic nightmare. However, the stakes were too high, and the operation needed to continue without the distractions of Montgomery’s ego and demands.

After much deliberation, Eisenhower made the difficult decision to effectively sideline Montgomery. He would not grant Montgomery the additional resources and autonomy he had demanded. Instead, he reaffirmed his control over the campaign and emphasized the importance of maintaining unity and cooperation among the Allied forces. The relationship between the two men, already fraught with tension, was now irreparably damaged.

Eisenhower’s decision was not made lightly. He had to balance the needs of the war effort with the political realities of maintaining good relations between the British and American forces. But in this moment, Eisenhower demonstrated his leadership ability—not just as a military strategist, but as a leader who understood the importance of maintaining authority, unity, and discipline within the Allied command.

The Fallout: The Aftermath of the Decision

The fallout from Eisenhower’s decision to sideline Montgomery was swift. The British general, known for his confidence and sense of self-importance, was not pleased with the outcome. The tension between the two men only grew, and Montgomery’s reputation within the British military establishment took a hit. Despite his successes in previous campaigns, Montgomery’s inability to work collaboratively with the Americans during the campaign in Normandy would be a defining feature of his post-war career.

For Eisenhower, however, the decision proved to be the right one. The success of the Normandy invasion, followed by the liberation of Paris and the continued push into Germany, demonstrated the effectiveness of the unified command structure that Eisenhower had established. His ability to manage the complex dynamics between the British and American forces, even when personal egos were at play, was critical to the success of the Allied war effort.

In the years that followed, Eisenhower’s leadership would continue to be hailed as one of the defining factors in the Allied victory in World War II. Montgomery, while still respected for his past achievements, was increasingly seen as a man out of step with the needs of the post-war world. The rift between him and Eisenhower would serve as a reminder of the challenges that come with balancing military leadership, ego, and the need for unity during times of great crisis.

The Legacy of Their Conflict: Leadership Lessons from the War

The showdown between Eisenhower and Montgomery over the course of World War II serves as a powerful lesson in leadership. It’s a reminder that the ability to make tough decisions, even when they are unpopular, is what separates great leaders from those who are merely talented tacticians. Eisenhower understood that the success of the war effort required not just military strategy, but the ability to navigate the egos and personalities of the people he was working with. His decision to sideline Montgomery, while difficult, ensured the cohesion and effectiveness of the Allied forces.

The legacy of this conflict between two of the most prominent military figures of the war is a testament to the complexities of leadership during times of extreme pressure. The ability to make difficult choices and prioritize the greater good over individual desires is what ultimately leads to success in both wartime and peacetime.

A Moment of Strategic Clarity

When Eisenhower read the telegram from Montgomery, he knew that the stakes of the war—of the entire Allied campaign—were too high to allow for personal pride to interfere with the strategy. The decision to sideline Montgomery was a turning point, a moment when the power dynamics between two military giants shifted. In that moment, Eisenhower did what was necessary for the success of the campaign, and the Allied forces were able to continue their march toward victory.

The lesson of that decision resonates beyond the context of war. It speaks to the importance of leadership, unity, and the difficult choices that come with balancing personal relationships with the greater good. Eisenhower’s ability to prioritize the war effort over personal egos ensured the success of the Allied mission—and that, more than anything, was what ultimately secured victory in the Second World War.