How Did Japan Think It Could Beat the United States in WWII? An Analysis of Strategy, Ambition, and Miscalculation

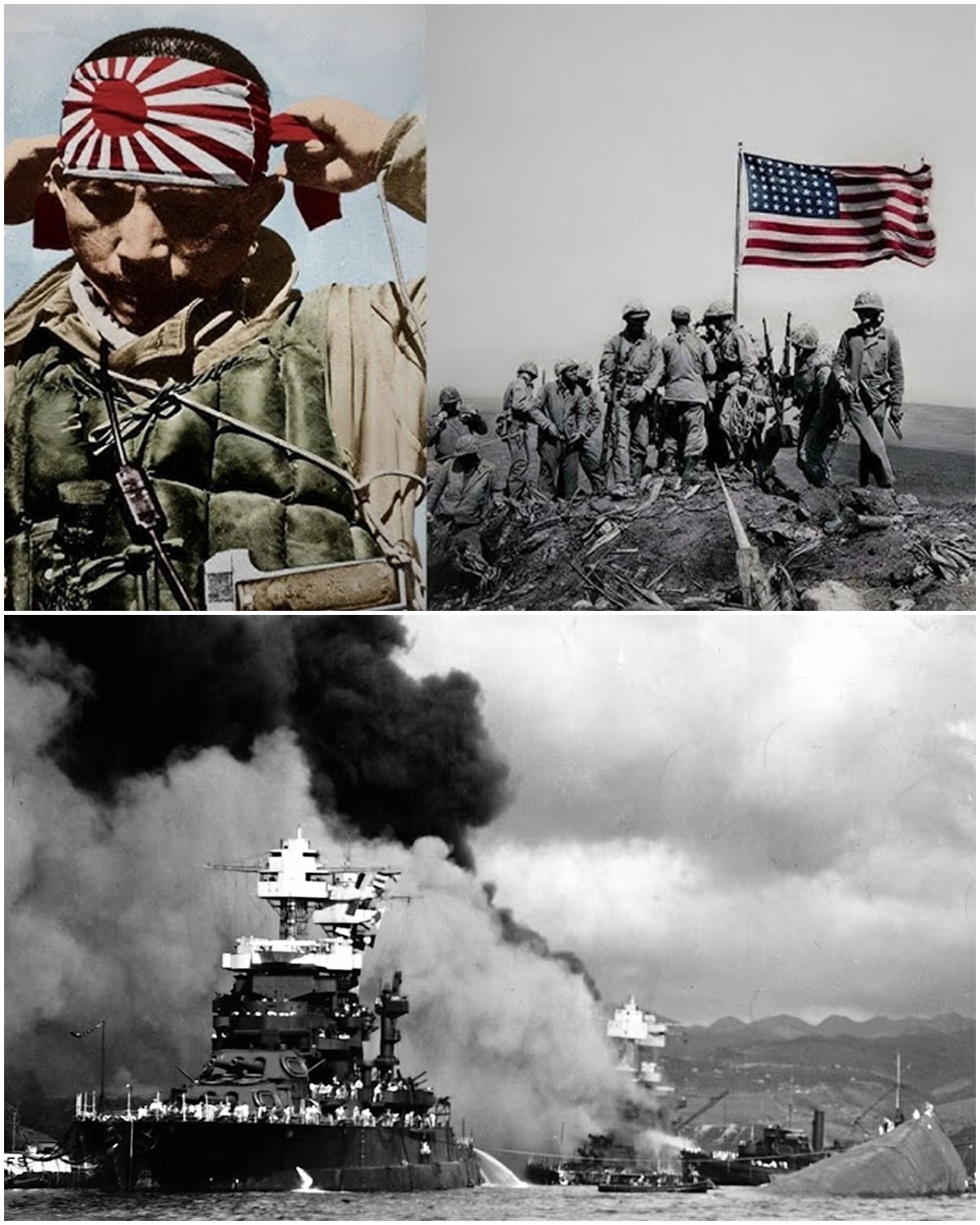

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, it did more than just provoke a response from the United States—it triggered the most consequential conflict of the 20th century. The attack propelled the U.S. into World War II, marking the beginning of a long and brutal war in the Pacific. However, the question remains: how did Japan, an island nation with a relatively small population and limited industrial capacity, believe it could defeat the United States, the world’s most powerful industrial and military force at the time?

At the heart of Japan’s decision to challenge the United States in World War II lay a combination of historical ambition, strategic miscalculations, and a deep sense of national pride. Japan’s leadership, especially under Emperor Hirohito and the militarist factions of the Imperial Army, believed they could achieve victory against the United States by using a blend of bold strategy, rapid expansion, and psychological warfare. Yet, despite early successes and strategic gains, Japan’s plan was riddled with flaws that would ultimately lead to its defeat.

In this article, we explore the thinking behind Japan’s strategy to defeat the United States in World War II, focusing on the key factors that led to its initial successes and eventual downfall. We will examine the military, political, and economic miscalculations made by Japan’s leadership and how their overconfidence and underestimation of the U.S. led to their undoing. Through this lens, we can better understand how Japan, a country that once seemed poised for domination, found itself on the losing side of history.

Japan’s Vision of Empire: Imperial Ambitions and the Need for Resources

The roots of Japan’s decision to challenge the United States lie in its imperial ambitions. For decades, Japan had been steadily expanding its influence in Asia, beginning with the colonization of Taiwan in 1895 and later Korea in 1910. But by the 1930s, Japan’s territorial ambitions had grown more aggressive. The country’s leadership, particularly the military factions within the government, saw expansion as essential to securing Japan’s place as a global power and ensuring its survival in a rapidly changing world.

The Japanese leadership viewed their territorial expansion as a natural progression—one that would provide them with the necessary resources to compete with the Western powers, particularly the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria in northeastern China, and by 1937, it had fully engaged in the Second Sino-Japanese War. These moves were part of Japan’s larger plan to build an empire across East Asia, what they called the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” The idea was to create an empire that would be self-sufficient, with access to the raw materials and natural resources Japan lacked, particularly oil, rubber, and minerals.

However, Japan’s rapid expansion brought it into direct conflict with the Western powers, particularly the United States, which had a significant interest in maintaining stability and access to resources in the Pacific region. By the late 1930s and early 1940s, Japan’s military leadership recognized that securing control over Southeast Asia, especially the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and Malaya, was crucial to the success of their imperial ambitions. These regions were rich in oil and rubber—two key resources Japan desperately needed for its military machine. The problem, however, was that these resources were also coveted by the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands.

As Japan’s expansion continued, tensions with the Western powers escalated. In 1940, the United States imposed an oil embargo on Japan in response to its aggression in China. The embargo put Japan in a precarious position—its military was heavily reliant on imported oil, and the loss of this critical resource threatened to cripple Japan’s expansionist goals. The Japanese government, particularly the military, saw war with the United States as inevitable if they were to maintain their empire and secure the resources they needed.

The Attack on Pearl Harbor: A Bold Gamble

By 1941, Japan had been engaging in small-scale skirmishes and territorial conquests, but it had yet to face the full might of the United States military. Japan’s leadership, however, believed that it could deliver a devastating blow to the U.S. and force a negotiated peace, securing its empire without the prolonged conflict that would drain its resources.

The decision to attack Pearl Harbor was a bold and highly risky one. The Japanese strategists believed that a surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet would cripple America’s ability to respond effectively to Japan’s expansion in Southeast Asia. The hope was that by taking out the Pacific Fleet, Japan could secure its conquests and establish a defensive perimeter in the Pacific, making it too costly for the U.S. to challenge Japan’s newfound empire.

However, this plan was based on several miscalculations. First, Japan underestimated the American resolve and ability to recover from such an attack. While the destruction of the Pacific Fleet’s battleships at Pearl Harbor was a significant blow, it did not cripple America’s ability to wage war. The United States had a vast industrial capacity that allowed it to quickly rebuild its forces and produce the war materiel needed for a prolonged conflict. The attack on Pearl Harbor, instead of weakening American resolve, galvanized the U.S. public and led to the declaration of war on Japan.

Secondly, Japan underestimated the logistical challenges of sustaining a global war. Japan’s strategic vision was largely focused on the rapid conquest of resources in the Pacific and Asia, but it lacked the industrial base to maintain the war effort over the long term. Unlike the United States, which had an industrial powerhouse capable of producing vast quantities of war material, Japan relied on limited resources and was stretched thin across multiple fronts.

Strategic Miscalculations: Underestimating the United States

Japan’s early successes in the Pacific—starting with the attack on Pearl Harbor and followed by conquests in Southeast Asia, the Philippines, and the Pacific islands—were impressive, but they came at a significant cost. The speed and scale of Japan’s expansion ultimately left it overextended and vulnerable to counterattacks.

One of the most significant miscalculations made by Japan was its failure to recognize the immense industrial capacity of the United States. After Pearl Harbor, Japan believed that the U.S. would be too slow to mobilize and respond effectively. However, the United States quickly transitioned to a wartime economy, churning out ships, planes, tanks, and ammunition at an unprecedented rate. The sheer scale of American production, combined with the country’s vast manpower and technological innovation, made it clear that Japan could not outpace the United States in a protracted war.

Additionally, Japan failed to recognize the importance of strategic resources like oil. By 1941, Japan had secured much of the oil in Southeast Asia, but its control of these resources was tenuous and dependent on maintaining its hold over conquered territories. The United States, on the other hand, had a secure and vast domestic supply of oil, and it was able to sustain its war effort without the same vulnerabilities that Japan faced.

Another major miscalculation was Japan’s underestimation of American military leadership and the effectiveness of Allied strategies. The Battle of Midway in June 1942 marked a turning point in the Pacific War. Japan’s attempt to expand its naval dominance was thwarted by the brilliant strategy and intelligence-gathering efforts of the U.S. Navy. The loss of four aircraft carriers at Midway was a devastating blow to Japan’s naval power and marked the beginning of a shift in the balance of naval warfare in the Pacific.

The Endgame: Japan’s Struggle and Ultimate Defeat

By 1943, Japan’s military situation had begun to unravel. The United States, having gained momentum through victories like the Battle of Midway, started a series of island-hopping campaigns, systematically retaking territories and moving closer to Japan’s home islands. Japan’s inability to keep pace with American technological advancements, the growing strength of the U.S. Navy, and the immense industrial capacity of the U.S. began to spell the end for Japan’s imperial ambitions.

Despite their early successes, Japan’s lack of a long-term strategy, coupled with the failure to secure lasting control of critical resources, led to a series of crushing defeats. The United States’ decision to implement a strategy of relentless bombing raids on Japanese cities and industrial centers, combined with the effective use of naval power, gradually wore down Japan’s ability to sustain the war effort.

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, coupled with the Soviet declaration of war on Japan, forced Japan to surrender unconditionally, bringing an end to the Pacific War.

Japan’s Overconfidence and the Lessons Learned

Japan’s decision to challenge the United States in World War II was a product of overconfidence, strategic miscalculations, and a fundamental misunderstanding of the resources and resolve of the American military and industrial complex. Despite its early successes and the strength of its military forces, Japan ultimately found itself outmatched by the United States, which could mobilize resources, manpower, and technology at a scale Japan simply couldn’t match.

The war in the Pacific serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of underestimating an enemy’s strength, the importance of securing resources, and the critical need for long-term strategic thinking in warfare. Japan’s defeat was not inevitable, but its failure to adapt to the changing dynamics of global warfare and its reliance on short-term victories rather than sustainable strategies led to its ultimate downfall.

In hindsight, Japan’s belief that it could defeat the United States appears to have been a fatal miscalculation—one driven by ambition, national pride, and an overestimation of their own military prowess. As history shows, overconfidence in warfare can be as dangerous as underestimation, and it was Japan’s underestimation of the United States’ industrial and military capabilities that sealed its fate in World War II.